Book Review: A Hastiness of Cooks

by Margie Gibson

I’ve flirted with historic cooking for years, but somehow, the relationship never took off. I would get frustrated by arcane language and ingredients and turn to something more familiar and easier to cook. Cynthia Bertelsen’s new book, A Hastiness of Cooks, has provided the catalyst that just may spark a beautiful relationship.

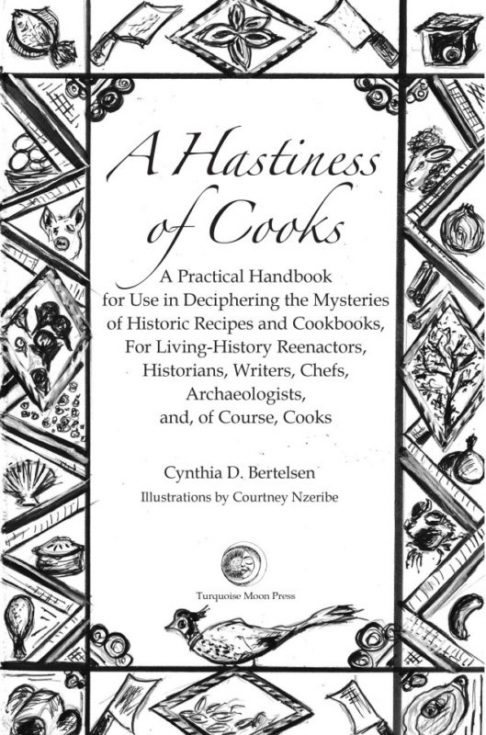

This slim volume’s subtitle, A Practical Handbook for Use in Deciphering the Mysteries of Historic Recipes and Cookbooks, For Living-History Reenactors, Historians, Writers, Chefs, Archaeologists, and, of Course, Cooks, precisely summarizes the book’s aims and audience. Courtney Nzeribe’s many illustrations remind the reader that the book’s ultimate subject is food and its preparation.

Bertelsen has provided the organizational structure and clarity that will help the reader analyze recipes from earlier centuries. This volume concentrates on the food on European tables from the Middle Ages to the 1700s. Spanish and English recipes get prime attention—after all, the territories that Spain and England conquered were huge and were the source for a steady stream of new foods entering the European repertoire. Interestingly enough, England, whose early cooks were influenced by France, Italy, Persia, the Iberian peninsula, and Turkey, led the way in the production of manuscripts on cooking—which suggests to me that British cooking may have gotten a bad rap in the years since World War I.

Why bother with early recipes? We already have plenty of easily accessible recipes based on ingredients that we can source easily from the farmers’ market or local supermarket. As Bertelsen explains, cookbooks contain a wealth of information beyond ingredient lists and instructions for preparation. Cookbooks can also provide clues to social, economic and political circumstances. They shed light on what farmers were producing as well as on trade relationships. They provide insight into the lives of ordinary people, something often ignored in historical studies that focus on the wealthy and powerful—and for the most part, on men. Cookbooks, particularly as they progress to the 17th and 18th centuries, illuminate women’s lives, which were generally ignored as being less interesting than their male counterparts.

A Hastiness of Cooks also illustrates how early cookbooks were used. Food and medicine were intertwined and many early cookbooks contain recipes for the sick and infirm, which give insights into medical beliefs. Also, earlier books were intended for those in charge of managing wealthy households or the kitchens for abbeys and universities, so we are able to get downstairs insight into the mechanisms that fed large numbers of people.

Luckily for us, many of the early cookbook writers plagiarized . . . er, borrowed and shared . . . recipes during a time when European cuisines were not strongly differentiated from each other. Today, this is especially useful if a recipe in one book doesn’t make sense. By searching for similar recipes in other cookbooks, modern cooks can reconstruct the holes and lapses in earlier books.

In another very useful chapter, Bertelsen provides tips on how to begin recreating old recipes. She sets up a framework for analyzing the recipe, which helps resolve the questions and problems that might otherwise discourage the modern cook. She also describes cooking techniques, such as cooking on a hearth or in a fireplace, that have been lost in the modern kitchen. Anyone trying to create a living history cooking program at a folklife museum or colonial-era home would find a wealth of information here.

Perhaps best of all, the book explains how all these early resources can be interpreted for today’s kitchen. In Part IV, Bertelsen presents five Spanish and five English authors of cookbooks with a fictionalized, first-person description of the writers’ lives. These short blurbs are followed by an original recipe, as well as a transcription of the recipe. She uses her framework to analyze the text and produces a recipe that could be cooked in a modern kitchen.

Reading about these early authors, one sees how they influenced each other and how they were influenced by the Age of Exploration when so many new foods appeared in Europe. By the time I finished the final section about Hannah Glass’s book, I understood the analysis process and thought I could try my own hand.

Of course, I know there will be inevitable questions and roadblocks in my efforts. So for further perplexing problems that may vex the modern cook, the book concludes with a discussion of the importance of bibliographies and provides a rich selection of on-line resources for further reference.

I highly recommend this book, which is not only a fine instructional text but will be an excellent reference for questions that arise as I delve deeper into old recipes. In short, A Hastiness of Cooks is a goldmine that I fully expect to explore further in this developing relationship with historic cooking.

|

|

Leave a Reply