En Art, j’aime la simplicité ; de même, en cuisine. / In art, I like simplicity; the same goes for cuisine.–Erik Satie (Honfleur 1866-Paris 1925), in Cahiers d’un Mamifère.

|

|

En Art, j’aime la simplicité ; de même, en cuisine. / In art, I like simplicity; the same goes for cuisine.–Erik Satie (Honfleur 1866-Paris 1925), in Cahiers d’un Mamifère.

|

|

Kentucky is far from Chartres, but not so far as one might think. Biscuits and cornbread were the bond that held us together in Kentucky; wheatfields and bread do the same in Chartres. We like white gravy; the Chartrains, as they’re called, like sauce. Isn’t white gravy a sauce, after all?

Growing up in Kentucky, I embraced the Slow Food concepts without ever knowing it. Wendell Berry was my breakfast, lunch and supper, after all. The French have never fully embraced the official Slow Food concept of Good, Clean and Fair, since they consider that French cuisine and agriculture already embrace these values and do not need an organization – especially an Italian association with an English name – to teach them about their own time-honored traditions. One might say that the French are arrogant and chauvinist, which I would never totally deny, but it is this very pride that has maintained a high level of quality in the world of artisanal food and agriculture.

I have lived in the Beauce region, the bread basket of France, for over 15 years. The hill of Chartres is surrounded by wheat and grain fields and when you go to the bakers, they actually mark the name of the millers who provided the grain for particular breads. It’s all rather magical for those who have a holistic view of the world. The Beauce is all about farming, in particular, wheat, grain and sugar beets, but also goat cheese, pork products, rabbits, beer, apples and apple cider products, pears, chickens, rapeseed, etc. My goal has been to find all the best producers and growers and support them in every way possible.

|

|

Une ingénuité confite de vieille fille. / The preserved naivité of a spinster.–Colette, La Naissance du Jour / Break of Day

I like my man to be a bit confit. Confit is my favorite French word. It can mean many things, but the meaning always implies intensity to the point of being almost sweet, and sometimes sickly sweet.

The word comes from the Latin, conficiere, meaning “to do” or “to make,” and is the root of other familiar words like confiture and confection,” says Kate McDonough. “It can equally describe flavoring and preserving foods in other substances, as fruit in sugar, olives in oil, pickles in vinegar, or capers in salt.”

In the food world, there are two main meanings, although the term basically means “preserved;” there are, of course, many ways of preserving food. The first refers to something candied or crystallized, such as the fruits confits so popular in France, especially at Christmas and during other holiday periods. The second refers to a savory food either cooked in its own juices or preserved.

The French confit we know best is canard confit, or duck confit, which is traditionally cooked in a copper pot over a fire for up to 24 hours so that its fat oozes out and envelops it. It is then stored in its own fat and conserved in a jar for up to a year.

Pickles and salted capers also count as confits. Another common one is tomates confites, or confit tomatoes, which are slow-cooked like duck in a low-temperature oven until they become almost sweet like candy. Intense, yes.

|

|

Becoming a chef in France requires a long commitment, both in terms of schooling and on-the-job training. The program is similar to that of a vocational school, but requires many years of on-the-job experience before one can be called “chef.”

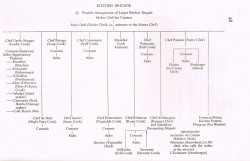

A typical French kitchen brigade looks like the diagram below. To become a chef, you basically have to work your way up from the bottom. Each level in the hierarchy may take a few years to master. It all looks rather daunting, but the French start young, around the age of 14, with chefs following what is referred to as a vocational track rather than a general high school.

|

|

French cuisine is much more than the haute cuisine inherited from the nobility. It is also the tasty, inexpensive cuisine that French families eat every day, called cuisine bourgeoise, or “bourgeois cuisine.”

We all learned in school that “bourgeois” was a social class. Originally, it was what we now call the “middle class,” as opposed to the nobility and the poor and working classes. The bourgeoisie, or middle class, grew rapidly in France after the French Revolution.

In terms of cooking, the bourgeois weren’t rich enough to use expensive ingredients and their cooking skills were not as highly developed as those of the aristocrats’ chefs, but they had sufficient means to entertain friends and family. This cuisine came to be known as cuisine bourgeoise, which today simply means family cooking, tasty but not pretentious, as opposed to the haute cuisine of the elite.

|

|

The New Year’s Eve celebration, referred to as Saint Sylvestre in France, is of pagan origin. The celebration existed long before St. Sylvester himself and long before there was even a pope. Ancient beliefs and celebrations, both religious and pagan, are mixed with those of winter solstice.

In Ancient Rome, the New Year was celebrated after Saturnalia, which was around December 25th, and was a time for “feasting, goodwill, generosity to the poor, the exchange of gifts and the decoration of trees.” People exchanged coins and medallions in celebration of the New Year. This tradition has slipped into oblivion, although adults sometimes still give children coins on this day, but other parts of Saturnalia continue today.

Up until the time of Julius Caesar, this end-of-year celebration didn’t have to fall on a fixed date; it was simply about ten days after Saturnalia. It was Caesar who set the date of December 31, and later, in France, Charles IX set the first day of the year as January 1.

St. Sylvester was Pope from 314 to 335, at the time the Church was emerging from the catacombs. Although Emperor Constantine controlled most of what went on in the Empire, Sylvester persuaded him to convert to Christianity and close the pagan temples. The great basilicas were also built under his influence.

|

|

The Yule Log, or the bûche de Noël, “an elaborate creation consisting of a rolled, filled sponge cake, frosted with chocolate buttercream to look like tree bark and festooned with meringue mushrooms, marzipan holly sprigs, spun sugar cobwebs and any other sort of edible decoration,” is the traditional choice of Christmas dessert in France. It comes in many flavors and pastry chefs and home cooks alike let their creativity go wild.

distopiandreamgirl via Foter.com / CC BY-NC-ND

|

|

Etre le dindon de la farce. / To fall victim to dupery.

Une dinde. / A stupid, pretentious woman.

Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, perhaps France’s best-known gastronomic writer, said that the turkey was certainly one of the most beautiful gifts the New World had given to the Old. “…the fattest, and if not the most delicate, at least, the tastiest of all domesticated birds.” It’s not often that the New World gets such compliments from discerning French epicures.

Turkeys were originally called poules d’Inde, “Indian hens,” in France, because they were thought to have come from India, which they later learned was Mexico. The French were not the only ones to get the name wrong. In Hebrew a turkey is a tarnagol hodu, meaning literally “Indian chicken;” in Russian indiuk, Polish indyk and Yiddish indik.

There is some controversy over who brought turkeys to Europe. Columbus probably brought brought them back in the early sixteenth century, since records show that King Ferdinand had ordered that every ship to bring back ten turkeys before the Spanish explorer Cortés set out in 1519. In any case, by 1548, they were the rage in France. In 1549, Catherine de Medicis served 70 “Indian hens” and 7 “Indian roosters” at a banquet held in honor of the Bishop of Paris.

French aristocrats were accustomed to eating all sorts of feathered creatures, including chewy storks, herons, peacocks, swans, cranes and cormorants, so it wasn’t surprising that they fell in love with the less-chewy turkeys, and that in 1570, Charles IX and Elizabeth of Austria thought turkey noble enough to serve at their wedding feast.

By the seventeenth century, the French were raising turkeys as if they were their own and most cookbooks included turkey recipes. French chefs weren’t lacking in ideas: they made stews and ragouts; they larded, roasted and glazed it; they stuffed it and made it into soups and pâtés.

Marie-Antonin Carême preferred the wings, which he deboned, then stuffed with chicken and truffles. Alexander Dumas, in his Dictionary of Cuisine, included 27 recipes. Turkeys were well established in the Hexagon.

Christmas dinners usually meant lots of mouths to feed, so turkey, being the largest of the winged creatures available, eventually became the dish of choice for Christmas feasts. By the nineteenth century, it became customary to stuff the Christmas turkey with chestnuts, and the tradition continues today.

|

|